The “riot” at Tule Lake sent shockwaves that whipped up anti-Japanese American fervor yet higher and fueled a Congressional inquiry within days. And yet, the preceding chain of events gives it and what followed an air of inevitability.

Armed Border Patrol agents were among the personnel who guarded the mixed-status Japanese Americans incarcerated at Tule Lake

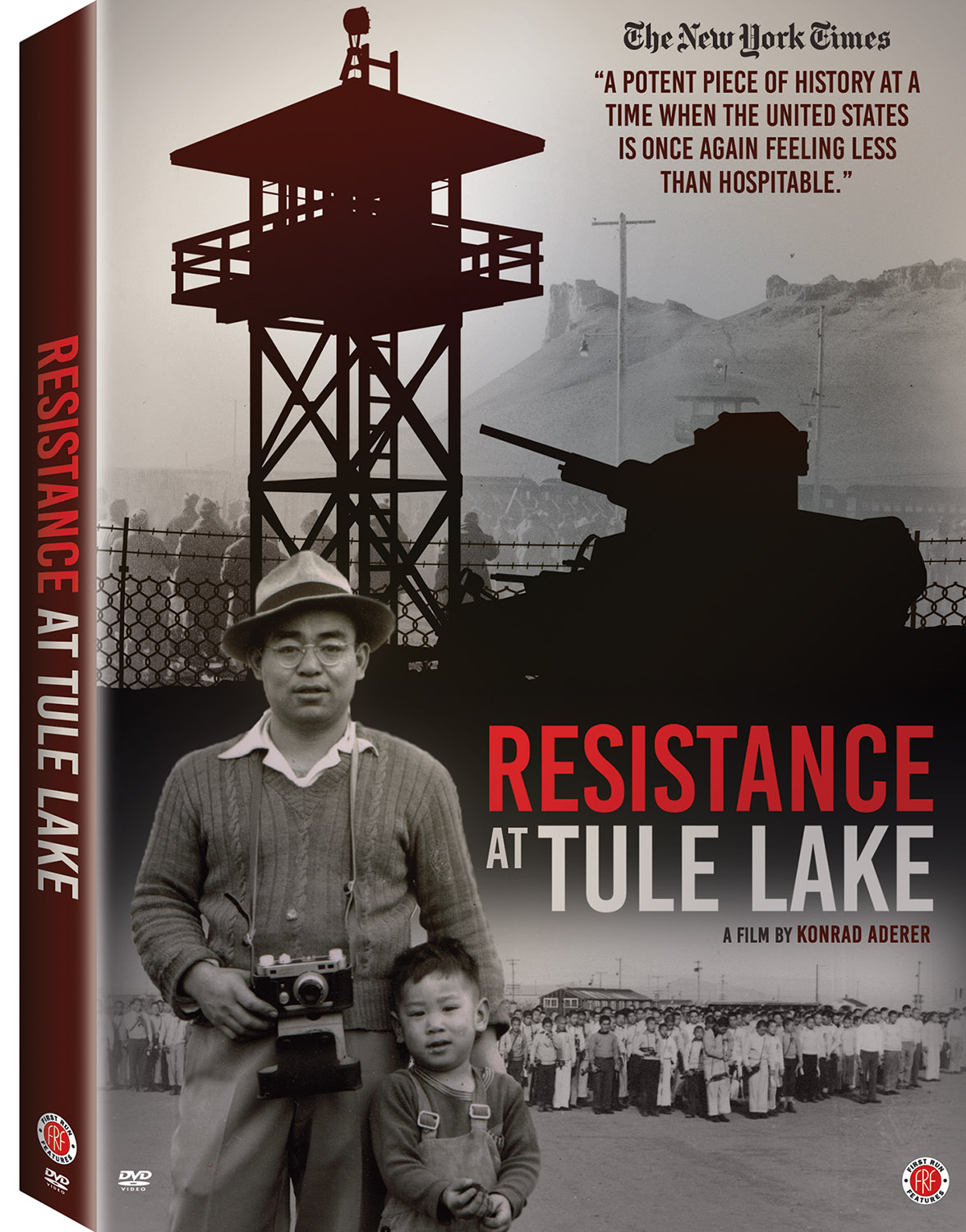

In July of 1943, the U.S. government designated Tule Lake as the camp for segregating all of the incarcerated Japanese Americans who had not answered “yes-yes,” to the Loyalty Questionnaire. A new Project Director, Raymond Best, took charge of Tule Lake. The authoritarian administrator was fresh from his prior job violating human rights as commandant of the Citizen Isolation Centers at Moab and Leupp. He immediately enhanced the punitive, militaristic aspects of the Tule Lake concentration camp, surrounding it with a new 16-foot-high barbed-wire fence. An entire battalion of the U.S. Army soldiers stood ready with artillery outside the perimeter. Six tanks, placed in plain view near the administration area, menaced the camp residents.

By September, over 12,000 “disloyal” Japanese Americans had poured into Tule Lake Segregation Center. Formerly scattered throughout ten concentration camps, the most assertive of the incarcerated Nikkei now lived in one place. Workers called two strikes in that period. Other urgent issues included food shortages and the incompetent, racist director of the camp hospital.

Freedom of assembly or riot?

Huge turnout gives weight to grievances

On November 1, 1943, a crowd estimated at 5,000 to 10,000 incarcerated Japanese Americans gathered around the headquarters of the Caucasian administration of Tule Lake Segregation Center. The crowd, which included many women and children, came in support of their elected representatives, called the “Negotiating Committee,” or Daihyo Sha Kai.

Enemies of white hegemony

George Toshio Kuratomi, a schoolteacher, presented grievances and demands to Mr. Best. These included safer working conditions for farmers, and an investigation into food supplies being taken out of the warehouse by Caucasian personnel. A witness gave a heart-rending account of the death of an infant who had fallen into scalding water. Dr. Pedicord had refused to allow her taken outside the concentration camp to a fully equipped hospital.

The spark that set off an Army invasion

As the meeting got underway, a report reached the administration that some young Japanese Americans had entered the hospital and beaten Dr. Pedicord. This single outbreak of violence became the pretext for the U.S. Army to occupy the camp. Tanks rampaged through the barracks, firing tear gas. The soldiers terrorized the imprisoned families, freely training 50-caliber machine guns on passing children. Word quickly spread of the “riot,” and newspapers across the U.S. ran stories filled with hysterical accounts of Japanese menacing the Caucasian personnel.

In these headlines we can see tendencies that persist to this day:

- Defining a large gathering of non-white protesters as a “riot.”

- Using a violent act committed by individual members of a non-white ethnic group as the pretext for state-directed violence against the whole group.

Helpful interpretation of events